Meh’s Origin Stories

Behind the Facebook and Instagram page called Reno Henna there is Meh, a 30-year-old Bangladeshi woman who came to Reno in 1997 as a young child.

“I like to consider myself as a Bangladeshi American,” she says. “I was born in Bangladesh, but was raised in America, in Reno. So I think I'm a little more American than Bangladeshi, I'm not sure.”

Born to a strict Bangladeshi Muslim household, her parents often did not allow her to go outside and play.

‘When I asked them for Henna cones, they would buy it for me, that's something I can do in my room or inside, just practice…when I wanted to play with my friends and they wanted to go outside, I would tell them, ‘Hey, I'll do some Henna and you stay inside we'll do this together.’ And I got them to stay and we would play inside and I would do their henna. And so that way I started practicing and I would just do it on myself all the time just to spend time,” she explained on how restrictions led to creativity.

She explains her name and says it s Al-Mehbuba which translates to ‘‘the beloved’’ in Arabic. “But when we immigrated to America, I had to have a first and last name, so it was split into Al, first name and Mehbuba, last name. Same goes for my brothers, Al Mehadi (the peace) and Al Mehtab (the moon). Imagine receiving a phone call in our household where they ask for Al, but all three of our names are Al and the callers can't pronounce any of our last names and they would have to go through the first three letters to finally find out who they're calling about,” Meh laughed.

“I had it flipped to [my] first name Mehbuba, from [my] last name Al in school because I hate being called Al. My older brother did the same. That's where Meh comes from. I didn't want to be called Al in school and Mehbuba was too difficult to say for everyone, so my 6th grade teacher stopped at Meh and said she couldn't pronounce anymore and would call me Meh (May). I love my name, the meaning behind it and everything about it and I wish more people would take the time to understand it and pronounce it. But I also understand how difficult it can be and have accepted my nickname that was forced on me to accommodate Americans at such a young age. I made sure to name my children small syllable names so it can be pronounced and not shortened. Some still have difficulty with it but no nicknames so far with them,” she said of some of the challenges of multiculturalism.

Initially Looking for Extra Income

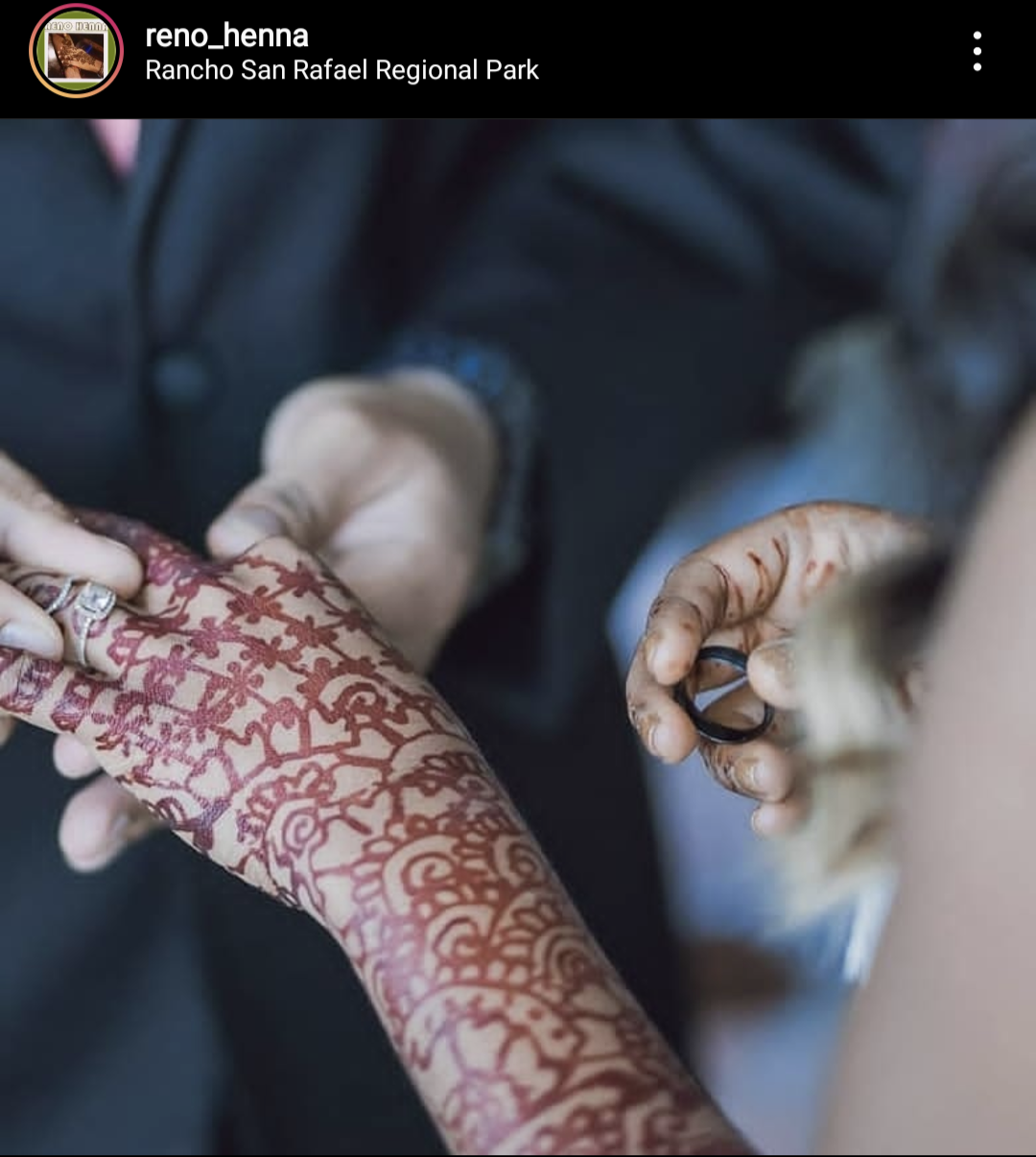

For those who are not familiar with it, Henna is a plant-based dye created from the Henna tree, scientifically known as Lawsonia inermis. It contains a natural coloring pigment which is often used for temporary body art, hair color, and to dye skin, fingernails or even fabric. Though it was widely used in Ancient Egypt it became most popular in South Asia. It is also known as “Mehndi” in some countries. A person’s body temperature along with the atmospheric humidity often helps in darkening the color and some south Asian bridal traditions have superstitious beliefs attached to it. The color is further darkened by the use of sugar concentrated water or clove oil to make it more long lasting on the arms and legs especially for wedding purposes.

Meh started her side business as a Henna artist about four years ago.

“I had a part-time job and was looking for some extra income…that was when Reno was becoming a bigger city with a lot of festivals. There's just a lot of events that go on in downtown, especially during the summer. And so I figured that maybe I can start doing it professionally to make that extra income and be a part of the community,” she said.

Since then she has put up her stalls at various events, including rodeos and cook-offs. She also takes part in birthday parties and shows up in her attire which consists of colorful traditional lehenga, beautiful dresses from south Asia or sarees. She says it is the “cutest thing” when little children or girls walk past her and exclaim, ‘Is she a princess’ when they see her.

Meh describes Henna to be a “poor person's business because in India and Bangladesh and the Middle East and Africa, we have Henna plants in our backyard and it's free, we just make a paste out of it.” However, for her own wedding when she was looking for Henna artists, as part of the tradition for the bride to be applying it on her big day, she found it to be very expensive.

“It's actually extortion, charging $500 for an arm…so I wanted to go against that and make it affordable,” she says. "“I don't want it to become a rich person's business. I want it to be affordable to anyone who wants it. So if they want a simple flower, if a child wants it, I'm not gonna charge more than five dollars for that. So what if I can't live off of it. It's more of a fulfilling part-time job that I do, but it's also for others to be able to afford it and experience it. This is something that comes from my culture as well. I can't hear the words from a mom saying I don't have money.If I hear a mom say that, I say, just come on over. It's fine.”

Covid definitely hit her small word-of-mouth in person business because she was initially unable to touch someone’s hand or draw on their palms but Meh says that unlike other winters she has had quite a few clients this season.

Not Afraid to Innovate

Meh does not specifically stick to motifs like flowers or leaves as per traditional Henna designs but has also engaged in experimenting with the art. She often goes into drawing skulls, skeletons and spiders during Halloween or just other designs like corsets and dreamcatchers. In traditional Bangladeshi or Indian weddings she has to mostly cater to the demands of the client while adhering to cultural aspects and hiding the name of the groom in the design drawn on the bride’s hand. However, she shares that her American clients are often as “happy” with a simple drawing of a heart.

“Americans are just so grateful...they sit right in front of me and they're like, ‘oh, is this okay? Like, is this gonna offend anyone?’ You don't have to do the designs that you normally do. They're very cautious and they're very respectful of our culture and what we've brought in. And I really appreciate that, but it's not something that one should fear whatsoever. Like Henna in the end is art. And whether you're doing it for your wedding or whether you just want a Disney princess for your daughter, I think that it should be appreciated and that a five year old, if that's all she wants, then let her have that happiness, no matter if she's American or Indian or not,” she said.

Apart from being a Henna artist Meh is also a mother of an 11-year-old daughter Arisha, and a one-year-old son Ayaan. She is currently pursuing general studies at TMCC and is a mentor in literacy programs with AmeriCorps. She dreams of having a career in the medical field eventually, she told me, while preparing a plate of nachos for her family.

Meh was married off at the very young age of fifteen, forcefully by her father, through an arranged marriage where she says she dealt with marital abuse. She gave birth to her daughter from her first husband when she was 19. Though she met her current husband Emerson at the age of 17, she was only able to settle with him in 2018, five years after she ended ties with her first husband.

Emerson Avecedo is a law enforcement officer who is African American, Native American and also Hispanic.

“My one-year-old is actually African American, he's Hispanic, he's Native American and he's Asian. So, I get to check all those boxes for him,” Meh says. “I've lived a lot in these last 30 years.” Meh said she would write a book someday and share her journey with many other women like her who might have been forced to be in a difficult marriage, as an inspiration to recover and find new wings.