“Any thoughts on the new Locomotion Plaza in #Reno where planting is now going on on the sides? Who will be using this space and for what purpose?” Biggest Little Streets (@OurTownReno) tweeted this on June 25. I shot back a zinger about “the collectivization of the psyche produced by art in public spaces,” and BLS invited me to write on the theme for here.

Maybe it’s because I grew up on film noir. What would a noir antihero say about Locomotion Plaza, even in black & white? Nothing. He’d flip his cigarette into the middle of it and turn away. So would the hat-check girl, the corner newspaper guy. I quit smoking forty years ago, but I still feel that way.

Denizens of the noir city were anonymous. City spaces gave privacy. You thought, I am in Chicago, New York, Los Angeles; you didn’t think, We are Chicagoans, New Yorkers, Angelinos. You didn’t say hello to strangers on those streets, even in neighborhoods canopied with elms. Of course the city of film noir was an illusion, an aesthetic antidote served on an industrial scale to citizens overdosed with collective identity by the national mobilization for World War II.

All the same, the noir city was based in everyday experience. We were only partway to where we are now. With exceptions such as ballparks, city spaces dictated privacy, and with it individuality. Not every coffee shop was a Starbucks. Shopping streets were lined with small businesses before row of franchises degraded the sense of place by making here indistinguishable from there. Air travel had only begun to decay our innate sense of location. Then came the interstates. What of the railroads, you ask, hadn’t they done the same? Yes. We’re always midway from one condition to another.

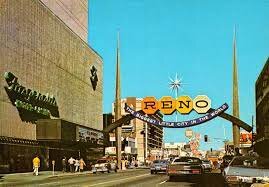

Reno was visibly midway when I first encountered it in 1963. The Biggest Little City was no longer, as its prose-poet laureate Walter Van Tilburg Clark well knew, the 1920s–30s “city of trembling leaves” which I came seeking. Much less was it the Comstock-era shipping and banking hub of its farther past. Not to speak of Truckee Meadows as the shared, contested ground of Paiute and Washeo, and they not its first inhabitants. Now in the age of globalization and the Anthropocene, artificial intelligence and climate change, smart phones and the blue planet, what use is it to bemoan the collectivization of the psyche? I’m whistling into the wind of change. Public art is the least of it.

But public art is a part of it. Setting aside that most of it is mediocre, on one level my reaction is visceral, literally physical as well as psychological. To be in the here and now with body-and-mind is to be located in continuous space, including urban space – by and large buildings are part of continuous space, relatively speaking. But art is not in the same space, art is an image, not reality (don’t quibble, you know what I mean). In public spaces, art intrudes on consciousness and breaks space, forcing us out of ourselves into collective identity.

Art isn’t alone. Billboards have the same effect, both their pictures and writing. Writing is a class of image, and public writing in any form which can’t be assimilated (a stop sign) breaches real space, draining its dimensionality and with it our sense of presence. And again, franchises: if Starbucks is Starbucks is Starbucks, where in reality am I? Who am I?

(As an aside, land art does the same thing to natural or wilderness spaces as public art does to urban spaces. They say there are no longer any “natural” places not impacted by Homo sapiens, and land art makes us constructively aware of it. Land art serves the preservation and restoration of the environment, they say. Maybe.)

I must qualify this diatribe by allowing that not all public art debilitates space and the sense of place. The whales in City Plaza are an exception. They trigger in the viewer an expansion of presence in real space by assimilating the plaza and its air space into the dimensionality of the imaginary water world surrounding mother and calf. It is a space maker. The BELIEVE sculpture, on the other hand, is a space breaker.

Art in and around public buildings largely gets a pass, because we integrate it into our perception of the building. In Reno, if you haven’t already, go see the mural (1930s) by Robert Caples in the Washoe County Courthouse, the lobby mural (1960s) in the Young Federal Building by Richard Guy Walton, and the steel sculpture (1990s) by Michael Heizer on the lawn of the Thompson Federal Building. It is both fitting and ironical that these halls of justice and power all have artworks treating Native American themes.

This brings me to the social and political ramifications of public art. My reply to the tweet from Biggest Little City asked: “Who benefits from the collectivization of the psyche produced by art in public spaces? Are we community or are we customers? Participants or peripherals? Citizens or subjects?” Beautification projects, artistic and otherwise, generally get done in city centers and trendy neighborhoods – your medians with planters, your riverwalks. Whatever good accrues to the private citizen from them, it’s hard not to believe that the powers that be arrange them basically for the financial benefit of – the powers that be. Make the place attractive to corporations, let them be able to recruit executives and middle managers.

“Art is the way you package the city,” Mayor Hillary Schieve said recently. “It’s really about creating more economic development.”

Sure this brings jobs, some. Mainly it brings money to money. In the upshot, cities everywhere come to resemble corporate campuses and each other, physically and functionally. The process only reinforces the homogenization of public spaces and the collectivization of the individual psyche. Did I mention surveillance cameras?

A footnote: Some public art carries a message of resistance. And some becomes a target of resistance, as in the takedown of Confederate generals on their horses.

Above, a photo with permission to use by Kelly Milan, of The Light of Truth Ida B. Wells National Monument, created by famed sculptor Richard Hunt, unveiled in Bronzeville, a neighborhood in Chicago, on June 30, 2021.

Another footnote: Its name aside, the film “noir” city of my nostalgia had precious few Blacks in it. For people of color the urban environment carried a different sense of danger from that which tantalized white audiences.