Getting Started

For Claire Holden, a student at the University of Nevada, Reno, studying environmental science, searching dumpsters behind grocery stores for viable food was not an unfamiliar task. The labels would have expiration dates that had not yet come, plastic boxes remained air-tight and closed, and produce would glisten from being freshly washed, despite some dents and imperfections.

These dumpsters were able to provide what thousands of people in Reno seek every day but are unable to find or afford: fresh food.

This reality is not unique to Claire. Housed and unhoused people all throughout Reno have found themselves in increasingly difficult circumstances exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and recent inflation.

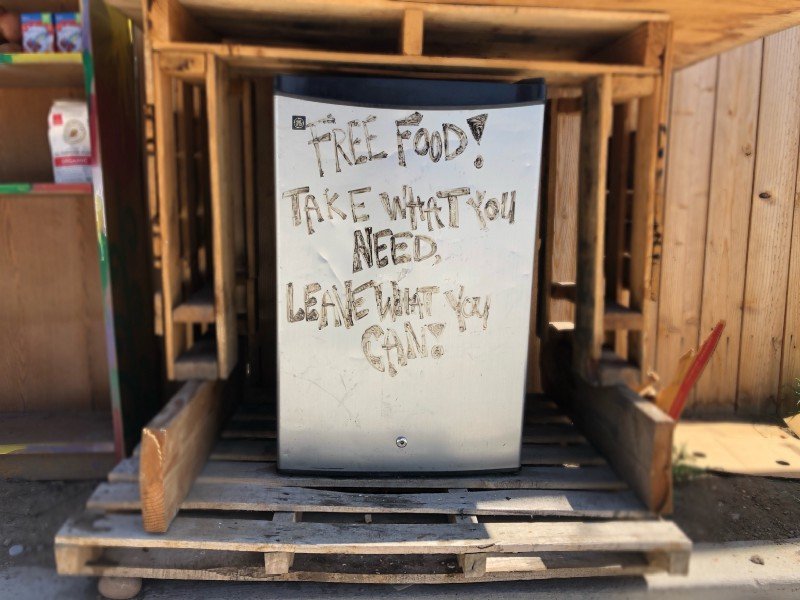

While the fight to end food insecurity in the Biggest Little City may sound daunting, Claire did not let that stop them from grabbing an extension cord, hooking up a mini-fridge and creating a free pantry, right in their own front yard. The message of the pantry was simple: take what you need, leave what you can.

And the Biggest Little Free Pantry was born.

The official logo for Biggest Little Free Pantry, designed in September of 2020, made approximately two months after the Instagram for the pantries was created. Art by Reno tattoo artist and ceramicist, Summer Ester, who can be found on Instagram as @waxmouth.

Lived Experiences Lead to Initiative

Claire Holden is a university student who works with several food recovery networks and local farms to combat food insecurity in Reno. Their passion for food recovery and food waste reduction comes from their own past experiences as a financially independent student who faced barriers when it came to feeding themself.

“It comes from a very personal place. I have, at times in my life, been houseless, I have not had access to food, and I’ve seen friends go through that same thing,” says Claire.

“I view food as such a bonding experience, you know, being able to share a meal with the people you love and the people around you and it’s honestly one of my favorite parts of my day.” Claire expands that food ought to be a right rather than a privilege. “I really think everyone deserves that, I view that as a human right. Everyone to some extent should have access to some form of nourishment throughout the day.”

After setting up a pantry in their yard, Claire made an Instagram to raise some visibility within the community. The expansion of these pantries began with simple word-of-mouth. Claire reached out to their peers and friends that they met through other food recovery projects, along with community members who had the means to help keep the pantries stocked. Claire said there was an “overwhelmingly positive response from the community” and people reached out in hopes of becoming a pantry host.

Some offered additional supplies to build or store food- including mini-fridges- while others offered their property to set up a pantry. “So in the time span of six months, I had four hosts and four pantries for the community to use,” shares Claire.

Biggest Little Pantry Founder Claire Holden (they/them) pictured with several bundles of kale at a local farm. They attend the University of Nevada, Reno as an undergraduate student in environmental science. Photo courtesy of Claire Holden.

Food Without Discrimination

One of the unique things about Biggest Little Free Pantry that separates it from many other food assistance programs, is the anonymity behind its usage.

The makeshift pantries are open to the public 24/7 and Claire and the other hosts make no attempt to monitor those utilizing the pantries.

Claire speaks as to why this privacy is a part of the mission. “There’s a really big stigma in really any form of government assistance, or getting help in any way when you are struggling. This helps make people feel a little less shame. I mean I remember when I was like 18 or 19 and I was in line at the food bank and I was terrified someone from school would recognize me or something,” Claire explains.

The stigmatization of food insecurity extends to students, parents, all community members alike.

“Even for families, they don’t want to show their kids how much they’re struggling and parents try to put up this really strong front. I think its important to have something that works to de-stigmatize that experience and it really can be used by anyone. You don’t have to be houseless, you don’t have to be living paycheck to paycheck, you can be anyone because everyone should have a right to food,” says Claire.

Jax Hart, the pantry host for the Sixth street location, shares similar sentiments behind the shame that tends to come with food insecurity. “Food insecurity doesn’t have a specific face, anyone can be hungry,” Hart says.

“I mean some people have the idea of ‘oh you have a house, you don’t need food’ but that’s not true, anyone can be food insecure so I really don’t like to police that usage at all,” says Jax. “I don’t care who takes food. In an ideal world food would be distributed evenly and the people that need it the most get it, but who are we to decide that and navigate that? So the food is for anyone. And if you have the means, come fill it up because there really is enough food out there and its just atrocious that people are hungry.”

Jax Hart is involved with several food recovery networks that work to mitigate food insecurity in the Reno-Sparks area. Photo by Vanessa Ribeiro.

FIghting for Food Justice and Food Equity

Jax Hart was already involved in several food recovery networks before they became a pantry host. “I think of all the food justice and food equity work I’ve been involved in, the [Biggest Little Free Pantry] is the best example of mutual aid,” shares Jax. “It’s just purely a tool for the community to take care of itself. It’s a network of relationships, not just a one-sided thing that makes someone feel good about themselves.”

The mutual aid framework allows the pantries to sustain itself through community contributions. Given the freedom behind who can use the pantry, it also means any person can drop food off, whether it be extra groceries after a trip to the store or spare food that restaurant has at the end of the night.

“A lot of food related work is charitable, it’s you coming from your place of privilege and money and you’re giving food to someone else, so it’s this very one-sided relationship. Whereas this is providing a space where the community can take care of itself. It’s not relying on my generosity, or someone else’s generosity, it’s reliant on the community taking care of itself. It's essential to whatever world we want for the future; we have to take care of our neighbors and each other because when it really comes down to it, who are the people you want to take care of and take care of you? It’s the people right around you.” — Jax Hart

A Biggest Little Pantry at 1135 Wilkinson Avenue. The pantry includes a wooden structure to protect the mini-fridge from the heat, and a shelving unit that contains food and products. Photo by Vanessa Ribeiro

Challenges in Working with Others

While this anonymity is integral to the accessibility of the pantries, it does come with its hurdles.

Claire says that many grocery stores who do food recovery are unable to work with Biggest Little Pantry due to the fact they don’t track or monitor who uses the pantries.

This makes the work of the hosts and community members that much more important for sustaining the success of these pantries.

“Instead of it being a place that’s just like a handout spot, the idea is that it’s a place that enables other people to help their community too,” says Jax Hart. “If you can’t get people to care about each other, how are you going to get them to care about anything else? If you don’t care about the people around you now, how am I supposed to expect you to care about people in 30 years?”

The fridge components of these pantries are protected by wood structures built by the volunteers of Biggest Little Free Pantry. These structures were made with plywood and fabric, with its pantry counterpart utilizing old book shelves and carts to store ambient items that don’t require refrigeration.

In the time spent at these pantries, numerous community members approached with hungry stomachs and open hands. There were men and women alike, of varying levels of trepidation when asked to conduct an anonymous interview. While some individuals chose not to divulge their experiences, two different community members who use the pantry were willing to share their stories.

The first was a 52-year-old male veteran who indicated he was unsheltered. The man had a mask around his chin and his finger nails clipped short. His face was clean but his hands were not. His clothes had a guise of professionalism- with a blue button up shirt and black khaki pants- that was betrayed by its faded print and creases that evidently came from sleeping on the ground overnight.

Sun spots littered the man’s face, and his eyebrows were so overgrown it was nearly difficult to find his eyes behind them; but they were there. Once found, his eyes shined bright blue with flecks of gold. They held many emotions, showing far more than what could be summed up in a fifteen minute interview.

An image of when Claire partnered with Reno Food Systems back in October of 2021; they allowed The Biggest Little Pantry to store donations in their walk-in freezer. Photo courtesy of Claire Holden.

Proud of His Community

When first asked to interview, the man’s blue eyes hiding behind a curtain of hair widened, a spark ignited at the opportunity to speak about his value to his community.

“I don’t wanna be here; on the streets, relying on others for survival,” he said. “I don’t wanna prove the people right in that the people on the streets take, take, take and never give. Well, you know what? I gave my all to my community and it’s because I didn’t get that in return that I’m stuck here today.”

He said he had been using the pantry for several months now. “I don’t really feel like my family is my family anymore, so [I’m] left to make my own family,” he says. “I don’t [know] who lives there,” he pointed to the front door of the house hosting one of the pantries, “but just by giving me this, they’re my family.”

The man spoke of the last two years being “absolute hell” due to the homeless camp sweeps Reno police officers were making in 2021. The constant relocation made it “difficult to feel safe.”

“Now? This community- my community- doesn’t expect anything from me. They’re kind and loving and fun for the sake of it, not because they want me to give [them] something in return. If people want to hate and judge me for relying on and making this community my own, then so be it,” said the man.

As those words left his mouth, his head raised a little higher; his chest seemed to pop out and his face dared to break out in a small smile. But again, it was his eyes that truly showed the pride for his community as he looked over to the front door of the pantry host again. “That is my community, and someone would have to be crazy and downright cruel to take that away from me.”

Food and drinks stored at the Wilkinson pantry location. Photos by Vanessa Ribeiro.

A Student on Hold

While the Biggest Little Pantries are undoubtedly used by those who are unsheltered, just like with the issue of food insecurity, these pantries’ are indiscriminate and can be a constant in any member of the Reno community’s life.

A 29-year-old college student stood at the pantry, eyeing her options of macaroni and cheese or mashed potatoes for her dinner. She had a green Jansport backpack that she used as a vessel to hold the food; it was tattered at the bottom and the straps seemed to be near threads as they supported the weight of the bag. It was difficult finding her eyes, too, but for different reasons. Like magnets, her eyes remained glued to the drawstring of her hoodie that her fingers fiddled with throughout the interview.

Her hair was cut, cleaned, and groomed, her nails sporting a chipped but fashionable sky blue nail polish. She had sneakers riddled with grass stains that matched the embroidered flowers on the edge of her boot-cut jeans. She looked her young age, but her words resounded as though she had lived a lifetime.

She began her studies at the University of Nevada, Reno, about three and a half years ago, transferring to the university after earning her Associates degree at Truckee Meadows Community College. Studying Human Development and Family Studies, she says her studies had to be put on hold during the pandemic.

“I was honestly lucky to even still have my job,” she says, “I knew so many people who were already in pretty low situations that had to then lose their job on top of that… there’s really only so much one person can take.” The woman was working in food service until February of 2022, but has since moved on to an office job in order to make a more stable form of income.

She said that after undergoing a bout of COVID, she was backed up on bills and classwork after having to take several weeks off of school and work. “I needed more money to survive, and unfortunately, the progress of my degree had to be put on hold in order to do that. A lot of my income came from tips so my job really required me being present in order to really have a sustainable wage. Having to catch up from that took a long time, and, obviously,” she gestured to the box of mac n’ cheese in her hand, “ I’m still kind [of] catching up,”

Despite the pause in her studies, the woman stressed the importance of completing her degree, “I’m not going to let the loss and tragedy of the last two years erase all the work I’ve done. I’m just as deserving of that recognition as anyone else.”

As the woman shared her experiences, her voice was quiet but didn’t falter. Her style and clothing were youthful, but her words were sensible and articulate. She told of her past with confidence that comes with remaining grounded with the present.

“I am so much more than my income status or the size of my home. I am a living, breathing, person and if the whole community had an ounce of the compassion that’s necessary to donate food, then maybe we wouldn’t have so many people struggling in own neighborhoods.”

The woman, who now had tears welled up in her eyes, finished her last statement with just as much poise as the start of the interview. She was fierce as she said, “I shouldn’t have to prove why I’m deserving of the compassion and love that lets humans and neighborhoods operate. I will give back when I have the means to do so. In the meantime, I don’t think anyone should hold it against any living human for relying on their fellow humans.”

“That’s just hurting your own community.”

This marketing logo was created to advertise the Sustainable Nevada Initiative Fund (SNIF) designed by prior ASUN Director of Sustainability Brita Romans.

The Next Step: The Sustainable Nevada Initiative Fund

After two years of mutual contribution, Claire thought it was time for a an upgrade for these pantries. But with makeshift structures built from donated scrap wood, it was difficult to imagine what the group would even start with.

At least it was at first; then came along the SNIF (talk about a fun acronym, huh?)

The SNIF stands for the Sustainable Nevada Initiative fund, which is awarded every year by the Associated Students of The University of Nevada, Reno (ASUN). ASUN is the student government organization that represents all undergraduate students at the university. With their near three million dollar budget of student fees, 15,000 is provided for the SNIF, with the ASUN Department of Sustainability implementing the selection process.

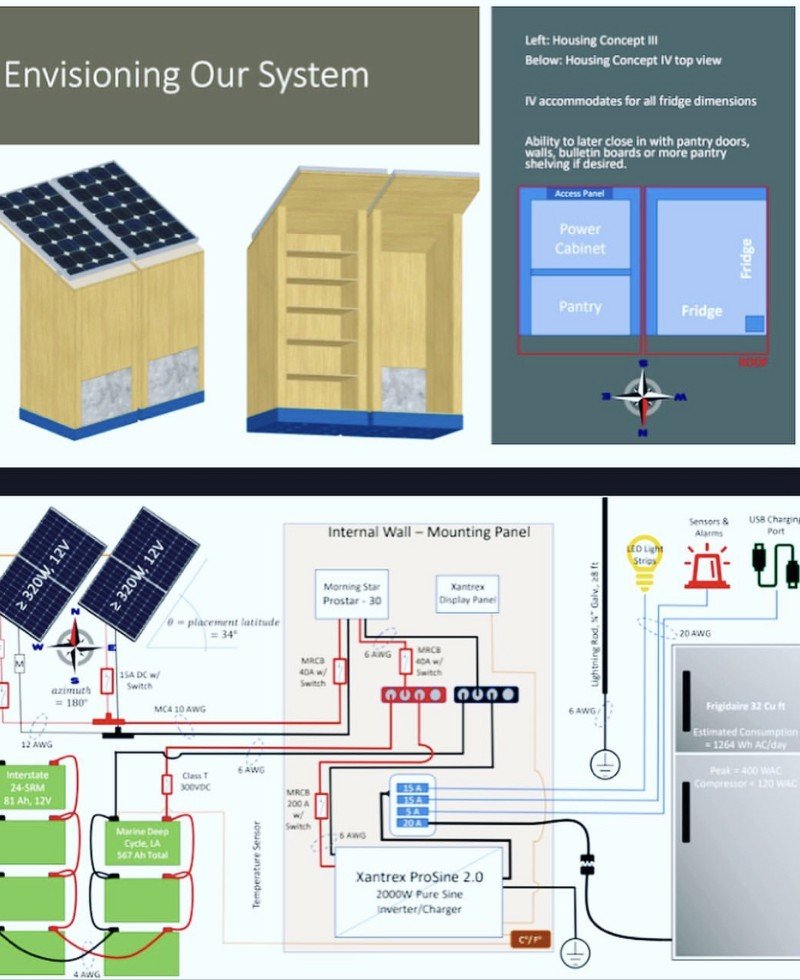

Claire has quite the plans to give these pantries new life, with the incorporation of full size refrigerators, external designs by local muralists and artists, and perhaps the biggest game changer: solar power.

“They’ll be solar powered, which is super cool because it takes off some weight from the host and makes it a little more autonomous,” says Claire. They also plan to built the pantries on top of large plastic pallets donated by Tesla. “It allows for more flexibility because all the hosts are actually renters, so it makes it easy for us to move the pantry in the scenario one of us has to move.”

A copy of the visual blueprint that Claire used in their SNIF proposal of the renovations they plan to make when granted with funds. The new design includes a full sized fridge on one side, with a pantry on the other. This new design includes the incorporation of solar power.

Getting Club Status at the University

With the expansion of and building of these pantries occurring over Summer 2022, Claire is planning on building up their volunteer base and club status at the university to create more infrastructure for The Biggest Little Pantries.

The current members who contribute to these pantries are all volunteers or community members who don’t receive financial compensation for their time or resources. Claire hopes to change that with the eventual establishment of non-profit status, “The end goal is non profit status instead of having to work through other people to get donations. Instead we can have someone get us food directly as representatives for us, and it allows some more freedom to work with The Biggest Little Free Pantries while also balancing other life responsibilities,” shares Claire.

Both Claire and Jax, as pantry hosts, have been able to connect and invest back into the Reno community through their involvement in the Biggest Little Free Pantry.

A Flawed System

Jax speaks to how each step made to feed those who need it, no matter how small, is a step in the right direction. “I think our system is very flawed, people are dying, people are starving, people are unhoused, people can’t afford medical bills, it doesn’t matter what my idea of the solution is, there are real every day issues that need to solves. But when I work with food, whether it’s distributing food directly or I’m working with a pantry, or I sort food at a food bank or something, it just… has such a direct impact.”

Claire feels that with the amount of food waste that happens in food service, industrial farming, and through general wastefulness, there are insurmountable environmental impacts, which creates human impacts. “This seems like a very easy and manageable mitigation strategy not only to food waste but also food justice,” Claire explains.

As they move forward feeding the community, one pantry at a time, the volunteers at the Biggest Little Free Pantry are seeing continued positivity and support throughout Reno’s food insecure population.

“I know it’s improving the material conditions of other people, almost instantly,” says Jax. “If someone needs food and they get food from this pantry, I mean that a huge amount of progress. I think it’s easy to get bogged down with trying to solve the world’s problems, but no one person can do that. But as one person I get another person food. And that’s tangible progress; even though it’s tiny tiny steps, it’s progress.”

The Biggest Little Free Pantries are at the following locations and can be found on Instagram at @BiggestLittleFreePantry: 1135 Wilkinson Avenue, Reno / 820 G. Street, Reno / 472 East 8th Street, Reno/ 523 East 6th Street, Reno