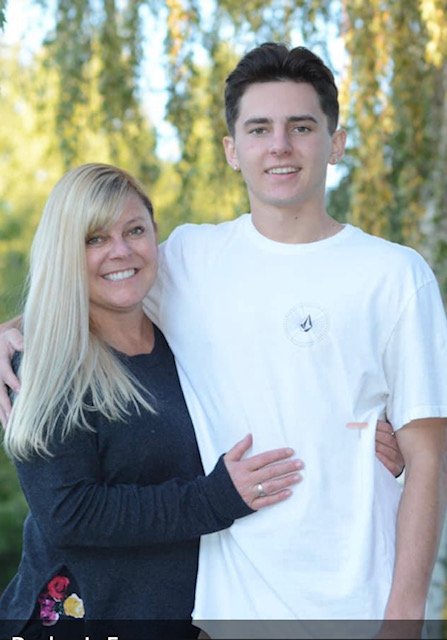

Debbie Bosco (right) with her son Hayden who died by suicide in 2020. Bosco felt there were many gaps in our systems which didn’t give him enough of a chance to overcome multiple challenges, which she now wants to help correct through her own initiatives.

While nearing retirement as a first grade teacher in the Washoe County school system and being a grandmother in action on evening nights, Debbie Bosco is starting to plan ways to honor her son Hayden, who died by suicide in 2020, just before turning 21, after battling for years with drug use and mental health challenges.

Debbie is thinking of starting an organization called Hayden’s Haven. One of her goals with this forthcoming organization will be to try to help improve how our local and national systems assist teenagers and young adults with mental health challenges. Another goal will be to offer informal friendly support for those going through these ordeals, including their loved ones.

“I want to have a place where people who are dealing with this age group, late teens to early adults, can go and just chill and maybe do trips, like skiing trips or something to get them outside. But just so they can be with other people and know that they're not alone,” Debbie explains.

“Hayden was so alone, he was the only one that he knew who had this, who was going through this. But there are other young adults going through this. And so I kind of want to create that for that niche as well as being able to give families a break because it's so hard on the families. I met another mom whose son is the same age as Hayden was and she's in the thick of it right now. And she's going through the same thing now. Now her son is in jail for attacking the dad.”

Helping this mother is bringing Debbie flashbacks. “You're a prisoner in your home. She's locking herself in the bedroom with her dog. I had to do the same thing.”

Hayden’s Haven will also advocate for wholesale change. “There needs to be help for the families as well as for these kids,” Debbie said during our recent phone interview. “They need to know they're not alone. They need to have more wraparound programs. There needs to be more funding. There's just nothing. And [this mom I’m speaking with] she's now getting the runaround. There's just no help and people don't call you back. And it's even worse when they turn 18 because you're completely helpless unless you have gotten some sort of power of attorney prior to that.”

Hayden was a popular three-sport athlete in high school whose life quickly derailed as a sophomore when he started hearing voices and feeling threatened.

Debbie remembers all too vividly the first morning he came up to her saying he couldn’t go to school. She later learned he had been consuming a lot of cannabis at the time and had dropped acid at a party.

“He told me that if he went to school, he wasn't going to make it out alive,” she said. “Obviously I'm freaking out as a parent. And he said he was hearing his friends tell him that if he went to school, he would not come out alive. I begged him to tell me who the friend was and when he gave me the name of his friend, who he was hearing it from, it was a friend who had taken his life the year prior.”

With her ex-husband, they decided to take him to the West Hills Behavioral Health Hospital, which is no longer around after shutting down in late 2021. There, Hayden did a three-day stint. Doctors diagnosed him with schizophrenia, a chronic brain disorder which, when active, causes delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, trouble with thinking and a lack of motivation.

“That’s what they believed it was,” Debbie recalls. “So, that led us in the direction of trying to find help for him. At the beginning we weren't really sure because he was smoking a lot of weed. So we weren't really sure if if that was causing it or if it was truly that diagnosis. So we went through a year or so of therapy, family therapy, just trying to get to the bottom of that. And then also trying to find a psychiatrist and a psychologist who would see him At the time he was 15, 16.”

Debbie said it was “nearly impossible” to find anyone to see him. When they did, doctors didn’t take the time to get to know Hayden and “it was just kind of medicine pushing, you know, prescriptions. Just trying to find someone that would actually see him was really hard. Like any sort of psychiatrist out there, they're either booked or they're not taking new patients.”

A year or so later, they started getting help at the Northern Nevada Adult Mental Health Services, known by its acronym NNAMHS.

“They had started a wraparound program where, if you could get into it, it consisted of a psychiatrist, two case workers and there was another counselor. One case worker kind of did more public stuff and then one just kind of monitored the paperwork type of thing,” she remembers.

The program was great but there was such “a high turnover rate that it was really hard for him to really bond with anyone,” Debbie said. “It seemed like it was kind of a stopping place for new doctors to, I don't know, if they had to do a certain amount of time in a certain place and then they could move on. No one seemed to stick around very long.”

This is also where Debbie noticed the case workers who really cared about the kids were the ones who were let go or were moved because they didn't follow all the rules. One of them she remembers fondly would have Hayden journal and take him to CrossFit classes and local parks.

The program then abruptly disbanded, Debbie recalls. “So then we were kind of back on our own. And in the, meantime he was struggling. Like he was struggling hard. He had very distinct voices in his head and some were voices of friends of his. At one point it was my voice in his head and everything that he heard in his head was very negative … it was talking about killing himself. There were no positives. Even though sometimes he would giggle and laugh at the voices, the negative took over.”

Hayden ended up graduating from high school by getting his GED at home.

But troubles escalated. Hayden started going to the house of one of his friends who he was hearing in his head, and slashing their car tires. While he got a restraining order, Debbie was trying to find another psychiatrist and teaching herself about schizophrenia.

She felt she was losing control, but no additional help from police or doctors was being provided.

“It was all very discouraging. Like everything was discouraging. They kept saying he had to hit rock bottom, he had to go to jail, he had to do this, and then there would be help for him.”

Hayden went several times to the Reno Behavioral Healthcare Hospital but as he was 18 by then, they would release him on his own with a bus ticket.

Hayden did an initial short stint in jail for choking Debbie, and she fought to lift a restraining order that was put on him so that he could live with her again.

Eventually he broke the restraining order against his friend, returning to his home. “The friend was there and then he snapped out of it. And Hayden called me frantically at work. I knew he would be arrested because he broke the restraining order and also he kicked in their door. So he did go to jail that time.”

He spent about three months in jail then, which Debbie says for “anyone with mental illness, jail is the worst possible place for them. He can't get his regular meds. They give them whatever they have on hand. And because he was 18, I could not get any information on him. And just every visit you could just see him declining. It was terrible. Like, it's just a terrible time. The only good thing that came out of it was that he was able to get released and get put into the mental health court.”

Established in 2001 by Nevada’s legislature, the court is designed to help people with a mental illness or intellectual disabilities, clearing their records if they complete rehabilitation programs. A doctor was assigned to him, as well as several case workers.

Hayden was in the program for a year, which included weekly drug testing, and stayed clean. Still Debbie was worried.

“He was really good on putting on a good face for other people. So they would never believe me. Like they kind of just would listen to him go by what he was saying in the 15 minute interviews they had, but not listen if I called with concerns because I knew something wasn't right with him.”

Hayden tried to live with his sister for a while, his father wanted to put him in the homeless shelter, but eventually he got housing through the mental court. After going to weekly meetings, and meeting regularly with doctors, he was graduated from the program in 2020.

But this is where Debbie believes the system failed him completely.

“We're in the middle of Covid. Everything now is over Zoom,” she said. “They graduated him and left him and me by ourselves on our own in the middle of Covid to find a new doctor, to find everything new. Like they just dropped us the minute he graduated. There was no other help after. And he took his life five months later. He moved in with me in June. And then he took his life in October of 2020.”

Hayden’s high school sports highlights can still be found online.

It wasn’t for a lack of trying to find new meaning and purpose, Debbie says. “It was doubly difficult because it was Covid and he couldn't form a bond with a doctor because it was all Zoom and he didn't know the person. And so now all the drug testing has stopped and all the meetings have stopped and everything has stopped. And he's just, you know, he tried to hold down jobs. He had some really great job opportunities, but in that mental state, you just can’t.”

His sister did a podcast and a tribute video for Hayden on YouTube (see above). “She didn't want him to be remembered as like this crazy kid who just took his life,” Debbie said. “She wanted people to understand what he was going through because he lost all those friends and he became a recluse. And it was just terrible. I watched the mental decline of my son.”

Debbie had gotten so desperate near the end of his life, she had even reached out to Dr. Phil, the television host for possible help, who actually contacted her, but the timing didn’t work for Hayden to go.

A screenshot from the tribute memorial video, with Hayden as a beautiful smiling boy.

Debbie views her son as a victim of a health care system which is too expensive and doesn’t care.

“I tried everything,” she said. “I looked into other states and the care is so expensive. If you want any sort of good inpatient care, it's totally unaffordable.”

She believes the mental health court system needs to be extended into even longer possibilities of housing with wraparound services, with patients given the time to find the right dosage and combination of medications.

“He never found the right medication,” Debbie said. “There really needs to be some sort of place that people can go that has that wraparound program that is funded well, that won't fizzle out and doesn't have such a high turnover rate of employees. They need those bonds. They need those connections with other people who actually care about it. They need a place that doesn't feel like a hospital, but they're still being cared for and monitored and can still feel like they're living a life.”

There needs to be more awareness in schizophrenia in general she says. “People won't talk about it. It's scary. You know, those are the crazy people who live on the street and I mean, I still have so much more empathy and compassion for them now, you know? When you hear snide comments, it's just, there just needs to be more education out there about it.”

Going back to old style asylums, where “it’s here's your medication, go to your room,” isn’t the solution either in Debbie’s estimation. “There just needs to be places where they can still be out in the open, like a trees park-like setting, maybe hold a part-time job, help them with transportation if they need transportation. Hayden was pretty high functioning. He had a car. He was able to get to and from the job, just he couldn't keep up with those eight hour days, that wasn’t working for him.”

In addition to a Hayden’s Haven program she has thought of herself creating a therapeutic location which she would call Hayden’s House. “I don't know the ins and outs of that yet,” Debbie said. “It seems a little daunting, but it's a future goal.”

In the meantime, she has found ways to reconnect with Hayden. “I listen to a lot of songs that remind me of him,” Debbie said at the conclusion of our interview.

“On my walks, anytime I see a raven or a penny, there's always some sort of significance with that. Can I feel him closer? I mean, I think that's kind of common for some people. I was there. I was the one who found him. So that was difficult. And I'm still in the same house, so I've turned his room into my office with a lot of his memories around it. So it's very calming for me when I go in there, which might seem strange, but it's gone from a place of sadness to a place of calmness. So I go into his room quite a bit and I'll write on his wall sometimes to him. I make sure on his birthday, to do something, which was November 12th and the day he took his life, which was October 9th, I'm always away. And then I put a little bit of his ashes somewhere so that this year it was Hawaii and then the year before it was Cabo. When he graduated the program, I was supposed to take him from somewhere tropical because he's always wanted to go. And being a single parent, I could never really take my kids on those type of vacations. So I never got the chance. So now my goal is every time I go somewhere I take him with me.”

Our Town Reno reporting, Spring 2023